By Robert Kolb

In John 14 [:8], where Philip spoke according to the theology of

glory, “Show us the Father,” Christ straightaway set aside his

flighty thought about seeing God elsewhere and led him to himself,

saying, “Philip, he who has seen me has seen the Father”

[John 14:9]. For this reason true theology and recognition of God

are in the crucified Christ.1

Of all the places to search for God, the last place most people

would think to look is the gallows. Martin Luther confessed

that there, in the shadows cast by death, God does indeed meet his

straying, rebellious human creatures. There God reveals who he is;

there he reveals who they are. Not in flight beyond the clouds, but

in the dust of the grave God has come to tell it like it is about himself

and about humanity.

In late April 1518 Luther’s monastic superiors summoned him to

Heidelberg to explain himself, at an assembly of the German Augustinians.

He did not comment on the issues that had gotten him

into trouble with the church, his critique of indulgences or his defi-

ance of ecclesiastical authorities.He cut to the quick and talked about

the nature of God and the nature of the human creature trapped in

sin. His assertions on these topics constituted a paradigm shift within

Western Christian thought in the understanding of God’s revelation

of himself, God’s way of dealing with evil, and what it means to be

human. His Heidelberg theses floated before his monastic brothers a

new constellation of perspectives on the biblical description of God

and of human reality. Luther called this series of biblically-based observations

a “theology of the cross,” and he later called this theology

of the cross “our theology.”2 “The cross of Christ is the only instruction

in the Word of God there is, the purest theology.”3

What he offered his fellow monks in Heidelberg was not a treatment

of a specific biblical teaching or two. He presented a new conceptual

framework for thinking about God and the human creature.

443

LUTHERAN QUARTERLY Volume XVI (2002)

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 443

He provided a new basis or set of presuppositions for proclaiming the

biblical message. Luther stepped to the podium in Heidelberg with

an approach to Christian teaching that came at the task from an angle

significantly different from the theological method of his scholastic

predecessors. They may have disagreed among themselves on a range

of issues, but they all practiced a theology of glory, according to the

Wittenberg professor. Luther called for a different way of thinking

about—and practicing—the proclamation of the gospel of Jesus

Christ. Indeed, more than a proposal for a codification of biblical

teaching, a theology of the cross, Luther called for the practice of this

theology in the proclamation and life of theologians of the cross.

However, Luther’s followers in the sixteenth century very seldom

talked about their theology as a theology of the cross, and they preserved

this new orientation for addressing theological topics only

partially. They had no intellectual equipment for the analysis of presuppositions

and conceptual frameworks. Melanchthon had taught

them to think in terms of organizing ideas by topic (loci communes),

and they presumed that all rational people would share their orientation

to the material. They took for granted that the inner logical

and theological structure of their thinking would be obvious to all.

Luther’s “theology of the cross,” however, is precisely a framework

that is designed to embrace all of biblical teaching and guide the use

of all its parts. It employs the cross of Christ as the focal point and

fulcrum for understanding and presenting a wide range of specific

topics within the biblical message. In Melanchthon’s Loci communes

theologici and similar works written by his and Luther’s students the

dogmatic topic “cross” treated human suffering,4 not God’s suffering

on the cross. Thus, the cross served a very different, and less allencompassing,

purpose than providing the point of view from which

to assess God’s revelation of himself, humanity-defining trust in that

revelation, the atonement accomplished through Christ’s death and

resurrection, or the Christian life. In subsequent Lutheran dogmatic

textbooks, this topic consistently treated only one aspect of the Christian

life, persecution and afflictions of other kinds.

If already in the sixteenth century Lutherans did not find Luther’s

theology of the cross particularly helpful, is it possible that Luther’s

use of Christ’s cross as the focal point for determining the dimensions

of biblical proclamation is even more out of date and distant

444 LUTHERAN QUARTERLY

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 444

today than it was four hundred years ago? For North Americans or

Western Europeans today the problem is not that we do not have

what God wants or expects of human beings (Luther’s problem). We

define the fundamental human problem differently than Luther did:

I do not have and receive what I want and expect—and I want to

know the reason why! Luther viewed God as the divine power that

was altogether too present in his life, as an angry demanding parent.

We view God as a modern parent, neglectful, absent, too little concerned

about us to be of much use. Luther’s theology of the cross

evolved from a concern that human creatures do not have—they

cannot produce!—what God in his justice demands from them.

Modern people complain because God does not produce what they

demand as their rights from him.

Some might therefore argue that the gap is so great that Luther’s

paradigm for the practice of theology as theologians, thinkers, under

the cross has itself become outmoded. In fact, Luther’s theology of

the cross reproduces for every age the biblical message regarding who

God is and what he does—and regarding the characteristics his

human creatures have—beneath the superficial fluctuations of history

and culture. The theology of the cross does more than address

the fleeting problems and miseries of one age. It refines the Christian’s

focus on God and on what it means to be human.

Theology of Glory,Theology of the Cross

Luther’s theology of the cross developed in his Heidelberg Theses

and in his great work of 1525, On the Bondage of Human Choice.

Summarizing this framework for the practice of all theology must

begin by distinguishing it from a theology of suffering and from a

theology of glory.5

First, the theology of the cross is not a theology that simply supplies

good tips on how to cope with tribulations and tragedies.Luther knew

alot about human suffering,but he never became fixated on suffering,

nor on blessing.His faith fixed his attention on God.Luther knew how

to give thanks to the Lord, not only for his grace and goodness but for

the all the necessities and nourishment of the body, for family and good

government, for good weather, good friends, peace, health, for music

LUTHER ON THE THEOLOGY OF THE CROSS 445

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 445

and a finely crafted poem. He knew how to enjoy God’s creation, also

with a song on his lyre. But Luther also knew that there are times in

the course of human events when guitar music is not appropriate.Physical,

emotional, spiritual suffering all fell to him as lot in life with some

frequency, and so he was very realistic about the evil of suffering—as

the deaths of two of his children overwhelmed him, as he felt betrayed

by a beloved student, Johann Agricola, as he coped with the pains of

his own body, as his anger and discouragement over the failure of Wittenberg

citizens to live under the power of his proclamation drove him

out of the town. But human suffering in itself was not the focus or

function of the theology of the cross.

What then is this theology of the cross? Luther says that it is the opposite

of a theology of glory. Theologies of glory presume something

about God’s glory, and something about the glory of being human.

First, medieval systems of theology all sought to present a God whose

glory consisted in fulfilling what in fact are fallen human standards for

divine success: a God who could make his might known,could knock

heads and straighten people out when they got out of line, even, perhaps

especially, at human expense. These scholastic theologians sought

to fashion—with biblical citations, to be sure—a God worthy of the

name, according to the standards of the emperors and kings, whose

glory and power defined how glory and power were supposed to look.

Medieval theologians and preachers wanted a tough,no-nonsense kind

of God to demand that they come up to their own standards for themselves

and to judge their enemies. They did not grasp that “lording it

over” others was the Gentile way of exercising power, not God’s.6

Second, out of his experience as a student of theology at the University

of Erfurt Luther suggested that these medieval systems of biblical

exposition taught a human glory, the glory of human success:

first, the success of human reason that can capture who and what

God is, for human purposes. Gerhard Forde observes that this glory

claims the mastery of the human mind in its investigations regarding

both earthly matters and God’s revelation of himself. “Theologians

of glory operate on the assumption that creation and history are

transparent to the human intellect, that one can see through what is

made and what happens so as to peer into the ‘invisible things of

God.’ ” For they attempt to construct their picture of God on the

basis of human judgments, abstractions that make universal some

446 LUTHERAN QUARTERLY

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 446

selected bits and pieces of the human experience and put human

epistemologies in charge of divine revelation.7

Alongside this glory of human reason, Luther found in medieval

theological systems an emphasis on the glory of human performance,

of works that can capture God’s favor by sheer human effort, plus

some help from divine grace. Religions of glory have as their first

and foremost goal the encouragement of good human performance.

The theology of the cross aims at bestowing a new identity upon

sinners, setting aside the old identity,by killing it, so that good human

performance can flow out of this new identity that is comprehended

in trust toward God. Therefore “the theology of the cross is an offensive

theology . . . [because] it attacks what we usually consider the

best in our religion,”8 human performance of pious deeds. A theology

of glory lets human words set the tone for God’s Word, forces

his Word into human logic. A theology of glory lets human deeds

determine God’s deeds, for his demonstration of mercy is determined

by the actions of human beings.

Although another element of Luther’s presuppositional framework,

his distinction between two kinds of righteousness,was not an integral

part of his Heidelberg presentation, it was developing about this

time, and apart from this presupposition Luther’s theology of the cross

will not come clearly into focus. Luther revised the theological paradigm

of discussing humanity when he posited two ways of being

righteous—two ways of being human—that must be distinguished to

understand the biblical definition of humanity. Human creatures are

righteous in God’s sight with a “passive”righteousness;we are human

in the vertical sphere of our lives only because of his mercy, favor, and

love, because he created us and re-creates us in Christ. At Heidelberg

Luther stated simply, “The love of God does not first discover what

is pleasing to it but rather creates what is pleasing to it.”9

Human creatures are righteous in relationship to each other and to

the rest of creation, however, with an “active” righteousness; it consists

in carrying out God’s commands to care for the world around us.

That means that human decision and human performance of all kinds

are designed for the horizontal sphere of life, where God has given us

stewardship for his creatures. When we attempt to use our decisions

and performance to please God—or some created substitute we have

made into an idol—we are taking them out of their proper sphere and

LUTHER ON THE THEOLOGY OF THE CROSS 447

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 447

laying upon them responsibility for making us God-pleasing. They

break under the weight of this falsely placed responsibility.

A religion dependent on human willing and human works is on

the prowl for the hidden God and will inevitably reshape God in our

own image. This kind of religion has nothing to do with the true

God. For it misunderstands the purpose and function of God’s law.

It attributes to the law the power to bestow life. In fact, the law only

evaluates life, Luther claimed. God gives and restores life. Thus, in

the midst of human life gone astray, the law—as God’s plan for what

human life really is to be and accomplish—“brings the wrath of God,

kills, reviles, accuses, judges, and condemns everything that is not in

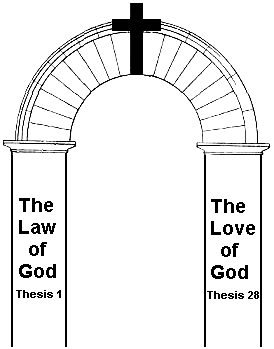

Christ,”10 including the noblest of human sinners, according to Thesis

23 of the Heidelberg Disputation. Forde comments, “Thesis 23

announces flatly that in spite of all the glorious hot air, God is not

ultimately interested in the law. The real consequence of such wisdom

is laid bare: The law does not work the love of God, it works

wrath; it does not give life (recall Thesis 1!),11 it kills; it does not bless,

it curses; it does not comfort, it accuses; it does not grant mercy, it

judges.” “In sum, it condemns everything not in Christ. It seems an

outrageous and highly offensive list. As Luther’s proof quickly

demonstrates, however, it comes right out of Paul in Galatians and

Romans.”12 Luther insists in the next thesis that the wisdom of the

law in itself is good. It is simply not to be used as a means of winning

God’s favor. Theologians of glory misuse the law in that way.13

Luther found these theologies of glory inadequate and insufficient,

ineffective and impotent.For such a theology of glory reaches out for

a manipulable God, a God who provides support for a human creature

who seeks to master life on his or her own, with just a touch of

divine help. That matched neither Luther’s understanding of God nor

his perception of his own humanity. Theologians of glory create a

god in their own image and a picture of the human creature after their

own longings. Neither corresponds to reality, Luther claimed.

Calling the Thing What It Is

“A theology of the cross calls the thing what it actually is,” he asserted.

14 The cross is the place where God talks our language: it is

448 LUTHERAN QUARTERLY

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 448

quite clear what is happening as Christ cries out, “My God,my God,

why have you forsaken me,” and dies. At the cross God meets his

human creatures where they are, in the shadow of death.For the cross

is not an instrument of torture but of death. On it people die. From

it Christ made his way back to life. That is where human beings can

see what God’s experience,God’s disposition—even God’s essence—

really are and what humanity really is, claimed Luther.

The theology of the cross involves not only the cross itself, as the

locus of the event that has determined human history. It involves also

the Word that conveys that event and its benefits to God’s people. The

word of the cross is folly to the perishing; this word is God’s power for

those whom he saves through it.15 Luther believed that when God

speaks, reality results. The cross and the Word that delivers it have created

a new reality within God’s fallen creation: a new reality for Satan

(since God nailed the law’s accusations to the cross and rendered them

illegible by soaking them in Christ’s blood); a new reality for death

(since it was laid to eternal rest in Christ’s grave); a new reality for sinners

(since they were buried, too, in Christ’s tomb and raised to new

life through the death and resurrection of the Crucified One).

To force Luther’s observations from the foot of the cross into four

convenient categories for easier consideration, it can be said that he

saw from the vantage point of the cross 1) who God really is, 2) what

the human reaction to God must be, 3) what the human condition

apart from God is and how God has acted to alter that condition,

and 4) what kind of life trust in Christ brings to his disciples.

1. God Hidden, God Revealed. Luther distinguished the “revealed

God” (Deus revelatus) from the “hidden God” (Deus absconditus), by

which he meant, in different contexts, either God as he actually exists

beyond the grasp of human conceptualization—particularly when

the human mind is darkened by sin—or God as sinners fashion him

in their own image, to their own likings. In addition, it must be noted

that the revealed God hides himself in order to show himself to his

human creatures. Luther observed that God is to be found precisely

where theologians of glory are horrified to find him: as a kid in a

crib, as a criminal on a cross, as a corpse in a crypt. God reveals himself

by hiding himself right in the middle of human existence as it

has been bent out of shape by the human fall. Thus, Luther’s theol-

LUTHER ON THE THEOLOGY OF THE CROSS 449

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 449

ogy of the cross is a departure from the fuzziness of human attempts

to focus on God apart from God’s pointing out where he is to be

found and who he really is.

In the Heidelberg Disputation, and in his expansion of its insights,

for instance in his Bondage of the Will, Luther focused first on the blank

wall created by the impossibility of human and sinful conceptualizing

of God; with fallen eyes no one can see God. With fallen human ears

no one can return to the Edenic hearing of his Word. Then Luther

focused very sharply on God in his revelation of himself:16 no one has

seen God, but Jesus of Nazareth, God in the flesh, has made him

known:a God with holes in his hands, feet, and side; the God,who has

come near to us, into the midst of our twisted and ruined existence.

This God on the cross reveals the fullness of God’s love as well as the

inadequacy of all human efforts to patch up life to please him.

2. Humanity Defined by Faith. Human attempts to claim God’s attention

and approval always draft a plan that tries to place God under the

control of human logic, or testing through signs of some sort or another.

17 People draw up job descriptions for God and become angry or

disappointed with him when he does not prove himself equal to their

tasks. Neither rational nor empirical proofs that would place God under

human domination can lead to God. God reveals himself through his

still, small voice,18 through the seemingly foolish and impotent Word

from the cross,19 in the Word made flesh,come to dwell among his people.

20 Luther’s theology of the cross is a theology of the Word of the

cross, a Word that conveys life itself on the power of its promise. Luther

insisted that trust alone—total dependence and reliance on God and

what he promises in his incarnation and in Scripture—is the center of

life, the living source of genuine human living. To recognize trust as the

core of our humanity is to perceive the true form of being human as

God created his human creature. That means that at the core of human

life our own performance, accomplishment, behavior, has no place. For

“a human work, no matter how good, is deadly sin because it in actual

fact entices us away from ‘naked trust in the mercy of God’ to a trust in

self.”21 Not trust in self,nor trust in one’s own logical or empirical judgment,

can constitute human life. God has designed life to center upon

trust in him. Heidelberg Thesis 25: “He is not righteous who does

much, but he who, without work, believes much in Christ.”22

450 LUTHERAN QUARTERLY

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 450

3. Handed Over for our Sins, Raised for our Justification. By showing

how God solves “the human problem,” the cross gives humankind its

best view of the nature of God,for it reveals his modus operandi, his way

of dealing with evil and reclaiming humanity for himself.Luther taught

that God’s true righteousness—his true nature, his essence—is revealed

in the cross, and it turns out that he is love and mercy.23 For God sent

his Son into this world to take sin and death into himself and to bury

sinners in his tomb.24 Apart from his sacrifice of his own life as the

substitute for his people under the law’s condemnation, there is no

life.25 Exactly how and why it is so is never explained in Scripture.

Forde warns against attempts to draft atonement theories that try to

elucidate the eternal truth behind the cross. “If we can see through the

cross to what is supposed to be behind it,we don’t have to look at it!”26

God’s Word simply presents us the cross. The fury of God’s wrath appears

there in all its horror. God’s anger reveals the horror of sin and

how it has ruined the human creature whom he loves. But that very

presentation of God’s wrath appears at that place,Golgotha,where God

has poured himself out in order to bury our sinful identity and give us

new life.Greater love has no one.27 Because of our sin God’s mercyseat

has taken the shape of the cross.

Sin is the problem. It is the original problem, the root of the problem,

the motor that drives the enmity between Creator and rebellious

human creature. Sin means the rejection of God and his standards

for being human. Rejection of God is the core kind of

sinfulness. Rejection of all the expectations that flow from his gift of

identity as his creature and child is the second kind of sinfulness. It

can be analyzed, or at least experienced, apart from acknowledgement

of the Creator. Death is a symptom of the problem. Disgust at

one’s own failures, discouragement because of the antipathy or apathy

of others, deterioration of health or memory or reputation are

all symptoms of the problem.Yet each of these symptoms can be the

point at which the cross begins to emerge out of the darkness and

come into focus. Any dissatisfaction with life and identity can form

the basis of conversation that leads to Calvary and to the heart of the

human dilemma. Even in a “guiltless” society the theology of the

cross provides the firm undergirding for discussion of topics that seem

distant at first, the topics of redemption or atonement.

For even sinners conscious of guilt cannot comprehend the overwhelming

extent to which sin has determined human existence after

LUTHER ON THE THEOLOGY OF THE CROSS 451

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 451

the fall. No one can grasp the enormity of the love of God that overcomes

the problem of sin and guilt. Luther rejected any cheap atonement

in which Christ bought off the enemies of his people with a

pittance of suffering, like a bit of gold or silver.28 He suffered unto

the death of the cross29 and thus met the law’s demand that sinners

die.30 But Luther not only depicted Christ’s saving act as a “joyous

exchange” of the sinner’s sin and death for his own innocence and

life.31 Luther also confessed that Christ had won the battle against

Satan in a “magnificent duel,” in which he inflicted fatal wounds on

Satan, sin, and death.32 God at his most glorious, in his display of the

extent of his mercy and love for his human creatures, appears, Luther

believed, in the depth of the shame of the cross. There he is to be

seen as he really is, in his true righteousness, which is mercy and love.

There human beings are to be seen as those who deserve to die eternally

but who now through baptismal death have the life Christ gives

through his resurrection, forever. For it is not true that Luther’s theology

of the cross excludes the resurrection. “A theology of the cross

is impossible without resurrection. It is impossible to plumb the

depths of the crucifixion without the resurrection.”33 He died for

only one reason: that his people might have human life in its fullest.34

Only at the foot of the cross can true human identity be discovered.

There, realizing whose I am, I realize who I am.

4. Take Up Your Cross and Follow. Finally,Luther understood that the

Christian life is not necessarily marked by earthly definitions of success

or suffering, by neither bane nor blessing, but instead is shaped by

Christ and his cross.35 Christ’s cross demonstrates that his people have

nothing to fear from any of their enemies,not even death itself. Therefore,

they are freed to risk all to love those whom God has placed

within the reach of their love.Having come to understand at the foot

of the cross what is really wrong with human life—not just its crimes

of magnificent proportions but the banality of our evils and the

wretchedness of doubt and denial of God—believers also recognize

from the vantage point of the cross what joy and peace come from living

the genuine human way in self-sacrificial love and giving.

Indeed, the theology of the cross is a paradigm for every human

season, also and perhaps especially, the beginning of the twenty-first

century, because it presumes and reasserts the biblical assessment of

452 LUTHERAN QUARTERLY

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 452

human life.Christian Neddens calls it “relevant and explosive” in its

application in twentieth century theology because it is, according to

the appraisal of Udo Kern, a fundamental norm for theological

knowledge and practice and therefore a “fundamentally critical theory.”

Neddens describes the critical function of the theology of the

cross in engaging objections to the Christian faith on the basis of

modern science and learning, and in regard to human autonomy and

human suffering. This theology serves as critical analysis for the misuse

of theology and a natural tendency toward theologies of glory.36

The theology of the cross functions as both a hermeneutical

framework and an orientation for theological criticism. It can aid in

sharpening the formulation of a host of questions, but this essay focuses

on its usefulness in discussions of “theodicy” and in defining

what it means to be human.

The theology of the cross clears the focus on human life, both as

it is misapprehended by those who try to think about humanity apart

from God,and as God reveals it through his own incarnation and his

death for fallen human creatures on the cross. In Luther’s theology

of the cross we encounter not only Deus absconditus—God beyond

our grasp, God as he can only be re-imaged by fallen human imagination—

and Deus revelatus—the only true God revealed in Jesus

Christ, who speaks to his human creatures from the pages of Scripture.

We also meet—though Luther never said it this way—ourselves,

first as homo absconditus—the human creature hidden from our own

eyes and assessment, in both our sinfulness and in the unexperienced

potential of humanity that sinners cannot grasp—and homo revelatus—

God’s perception, the only accurate perception and definition,

of what it means to be human.

What it means to be human is a question that interests Western

people of this age. Why life does not turn out better than it does, or

why God has disappeared, is another such question. If Luther’s theology

of the cross can aid contemporary searchers for haven and help

to understand the gap between their sense of what they could be and

their experience of what they are, it might be a message for moderns.

And if it could help explain why God, if he really does exist, falls so

far short of our expectations—if it can help us justify his treatment or

his neglect of us—then it might indeed be a theology for the twenty-

first century. These two aspects of the theology of the cross do not

LUTHER ON THE THEOLOGY OF THE CROSS 453

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 453

exhaust its sigificance and usefulness for guiding biblical proclamation

in this time, as Neddens shows, but this essay focuses on them as

examples of its contemporary significance and usefulness.

Deus Absconditus and the Cry of “Why?”

Deus Revelatus and the Response “Christ”

Luther’s theology of the cross developed out of his struggle with

the anger of God. But now the tables are turned: God is in the hands

of apathetic sinners. At the beginning of the twenty-first century people

struggle with the indifference of God but in this case turn-about

seems like fair play, for sometimes those who struggle most with the

apparent absence or indifference of God in their lives are those who

have not given thanks for a good bottle of Chateauneuf du Pape or a

sterling performance on the playing field, to say nothing of their very

existence. The burning question which Luther posed in the sixteenth

century regarding his standing before his Creator has turned into a

resentful complaint about God’s distance from anything important—

that is, anything that escapes our control—in our lives. People who

have believed in a Creator have thrown Job’s complaints back at the

Lord from time immemorial, but only since the Enlightenment have

self-confident human beings tried to engage in the attempt to justify

God’s indifference,impotence, inactivity in behalf of human creatures.

Three hundred years ago the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm

Leibnitz devised the term “theodicy” to describe the human

attempt to justify God by explaining evil. Theodicy is the attempt to

deal with a God from whom we expect all good things when he does

not deliver the good we expect. Although Luther was not addressing

the question of “how God could do such awful things to us” as he

formulated his theology of the cross in 1518,it speaks to the felt needs

of the twenty-first century people around us, at least in the West, to

explain evil—in hopes of mastering it.

1. God Has Come Near in the Blood of Christ. The theology of the

cross focuses our attention on the God who has come near to us in

the midst of our afflictions, not just with sympathy but with the solution

for the evils that afflict us. In the cross God has rendered his

verdict upon sin: it is evil, and it must be destroyed. And on the cross

454 LUTHERAN QUARTERLY

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 454

Christ destroyed our sin as the factor that determines our identity.

Luther did not fashion a justification for God’s permitting evil or his

failure to cope with it adequately. Bound to Scripture, he found no

more of an answer to the “why” of evil than that given to Job. He

simply let God be God. He trusted that the God who had come to

engage evil at its ugliest on the cross would triumph finally over every

evil. Therefore, he did not feel himself compelled to veil any part of

the truth about God or about evil. Theologians of the cross “are not

driven to simplistic theodicies because with Saint Paul they believe

that God justifies himself precisely in the cross and resurrection of

Jesus. They know that, dying to the old, the believer lives in Christ

and looks forward to being raised with him.”37 For God has “justified”

himself by delivering and restoring us to the fullness of humanity

through Christ’s self-sacrifice on the cross.

Luther’s On the Bondage of Human Choice sought above all to confess

that God is Lord of all. In that work he did not shy away from

those passages in Scripture in which God seems to be responsible for

evil. The reformer can be accused of trying to explain too much in

this work, and when that is true, he explains God in the way of the

Old Testament prophets who saw God at work in good and evil.38

But Luther did insist that human creatures dare not pry into the secret

will of God as he treated Matthew 23:37, Christ’s lamentation

over Jerusalem,39 and as he lectured on Genesis a decade after the

appearance of The Bondage of Human Choice, he did provide a corrective

to misimpressions he might have caused in his response to

Erasmus. In addressing the question of why some are saved and not

others, Luther there interpreted his earlier writing:

a distinction must be made when one deals with the knowledge, or rather with the

subject of the divinity. For one must debate either about the hidden God or about

the revealed God. With regard to God insofar as he has not been revealed, there is

no faith,no knowledge,and no understanding. And here one must hold to the statement

that what is above us is none of our concern. . . . Such inquisitiveness is original

sin itself, by which we are impelled to strive for a way to God through natural

speculation. . . . God has most sternly forbidden this investigation of the divinity.40

Luther then places in God’s mouth the following words:

From an unrevealed God I will become a revealed God. Nevertheless, I will remain

the same God. I will be made flesh, or send My Son. He shall die for your

sins and shall rise again from the dead. And in this way I will fulfill your desire, in

LUTHER ON THE THEOLOGY OF THE CROSS 455

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 455

order that you may be able to know whether you are predestined or not. Behold,

this is my Son; listen to him (cf. Matt. 17:5). Look at him as he lies in the manger

and on the lap of his mother, as he hangs on the cross. Observe what he does and

what he says. There you will surely take hold of me. For “he who sees me,” says

Christ, “also sees the Father himself ” (cf. John 14:9). If you listen to him, are baptized

in his name, and love his Word, then you are certainly predestined and are

certain of your salvation.41

Luther here goes further.He rejects any discordance between hidden

God and revealed God even though the hidden God goes far

beyond human grasp.

If you believe in the revealed God and accept his Word, he will gradually also reveal

the hidden God, for “he who sees me also sees the Father,” as John 14:9 says.

He who rejects the Son also loses the unrevealed God along with the revealed

God. But if you cling to the revealed God with a firm faith, so that your heart is

so minded that you will not lose Christ even if you are deprived of everything,

then you are most assuredly predestined, and you will understand the hidden God.

Indeed, you understand him even now if you acknowledge the Son and his will,

namely, that he wants to reveal himself to you, that he wants to be your Lord and

your Savior. Therefore you are sure that God is also your Lord and Father.42

The search for answers ends where the search for God ends: at the

cross, where God reveals his power and his wisdom in his own broken

body and spilled blood.43

2. Faith Clings to the Crucified One. Thus, Luther’s theology of

the cross focuses our attention on trust in the God who loves us

and promises his presence in the midst of afflictions. A doctoral

student of mine and his wife lost a baby shortly before birth a few

years ago.He related that a member of his congregation, trying to

offer comfort, had said, “Well,Pastor, at a time like this, all that theology

you’re learning does not do much good.” “In fact,” Mark observed,

“true comfort comes precisely from knowing the theology

of Martin Luther; it gives assurance that God is only that God who

shows love and mercy toward us. If we had to wonder what the

God behind the clouds really intends and why he is delivering this

evil upon us, doubt and distress rather than comfort would be our

lot. We cannot know why God took our child, but we do not have

to question how God regards us. He has shown us that decisively

in the cross.” The theology of the cross redirects our gaze from

456 LUTHERAN QUARTERLY

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 456

probing the darkness further and directs those who hurt and ache

to cling to Christ, whose love is certain and whose faithfulness is

beyond all doubt.

3. Evil Identified, Nailed to the Cross, Drowned in Christ’s Blood. The

theology of the cross reminds those caught in evil that evil is truly

evil, the opposite of what God wants for his human creature. It reminds

fallen human creatures that God has come to lift them once

again to true human life through his own death and resurrection. Instead

of justifying God’s failure to end evil today, or justifying human

actions that are truly evil, it justifies sinners so that they may enjoy

true life, life with God, forever. The problem with “theodicies” is

that they have to tell less than the truth, they have to avoid some part

of the problem, at one point or another. Whether they are working

at justifying God or justifying themselves, they always end up calling

what is truly evil good and what is good evil. In the final analysis,

sinners in the hands of an almighty God always find it difficult to

cope with what is not true, good, and beautiful. Instead of relying

on the person of the rescuer, the restorer of human life, they rely on

the explanations they have fashioned for mastering their problems.

The realism of Luther’s theology of the cross is able to confront

the horrors and the banalities of evil in all their perversity because it

enables us to avoid feeling obligated either to seek the good in evil

or to justify God.

Whereas the theologian of glory tries to see through the needy, the poor, the lowly,

and the “non-existent,” the theologian of the cross knows that the love of God

creates precisely out of nothing. Therefore the sinner must be reduced to nothing

in order to be saved. The presupposition of the Disputation . . . is the hope of

the resurrection. God brings life out of death. He calls into being that which is

from that which is not. In order that there be a resurrection, the sinner must die.

All presumption must be ended. The truth must be seen. Only the “friends of the

cross”who have been reduced to nothing are properly prepared to receive the justifying

grace poured out by the creative love of God. All other roads are closed.44

Waiting on God in the midst of the shadows creates the patience

that endures and fosters hope when believers can listen to his voice

through the darkness. For they know their Master’s voice and they

have confidence in both his love and his power.

LUTHER ON THE THEOLOGY OF THE CROSS 457

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 457

For God does not reveal the past of evil by explaining where and

why it arose, but he does tell us something of its present and everything

about its future.He comes to us as a God who has experienced

loss, suffering, and death, but he does not give answers as to the origins

of evil. The alternatives for solving that riddle seem to be two:

we are at fault, or he is at fault. The former justifies God, and we are

dead. The latter is an even more horrible solution: God gets pleasure

from our suffering. Instead of answers about evil’s origin, God

gives us his presence through the presence of his people and the

proclamation of his Word. He gives us the promise of the certain,

final, everlasting liberation from evil that he effected through Christ’s

resurrection.

4. Cruciform Humanity. The theology of the cross enables God’s

children to understand the shape of life as God has planned it for

them, following Christ under the cross. It provides the hope and

confidence that enables them to conquer evil in the lives of others,

as they follow the model Christ gives them. His atoning suffering,

death, and resurrection has conquered evil in their lives, and they recognize

their call to carry love into the lives of others—in some instances

through their own suffering and the bearing of burdens. True

“theodicy” is lived out in the lives, in the love, of his people as they

deliver it to neighbors caught in the grip of evil. That theodicic action

demands that children of the cross recognize the familial dimension

of their new life in Christ. Some evils may be combatted

by individuals, but most of the perversions of God’s plan for human

living have roots deep enough and facets numerous enough to demand

more than any one Christian can do to bring God’s presence

to the suffering. Not only the suffering but also the believers need

the support that comes from the larger company of Christ’s people.

In regard to their own struggles with evil, believers find in the cross

the reminder that they pose a false question when they demand to

know why the Creator does not treat them better. Finally, the expectations

of the human creature cannot demand more of the Creator

than he has promised. Indeed, his ultimate promise will bring

the end of all evil, but in the interim he has promised his presence

in the midst of evil, not its exclusion from our lives. Nor dare our

expectations of ourselves be less than God’s expectations of us.God’s

458 LUTHERAN QUARTERLY

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 458

promise of life and of his steadfast love suffice. The promise in fact

gives hope and joy and peace. It fosters a defiance of evil and the assurance

that the people of God can move through life on the solid

ground of the love Christ revealed on the cross.

Homo Absconditus and Homo Revelatus:

What It Means to Be Fallen and What It Means to Be Human

Luther’s Deus absconditus and Deus revelatus also reveals a great deal

about his understanding of what it means to be human. It might be

said that his anthropology taught both a homo absconditus and homo

revelatus.

1. “Human”Means Trusting God Above all Else. Being fully human

is first of all to recognize that God is the fundamental point of orientation

for humanity. Not to know him as Creator and Father imposes

bondage upon those who are created to trust in him. It enchains

them to their false gods, tyrants all. Sin springs from doubt

that denies God’s place in our lives and defies his lordship. Luther believed

that our sinful turning the center of our attention to ourselves

hides from our own view the depth of our own sinfulness, indeed

the nature of our own sinfulness. In the Smalcald Articles he wrote,

“This inherited sin has caused such a deep, evil corruption of nature

that reason does not comprehend it; rather it must be believed on

the basis of the revelation in the Scriptures.”45 The heart of the

human failure to be all that we can be, according to Luther, consists

of our failure to fear, love, and trust in God above all things. Both

sinners whose behavior openly defies God and the “wise, holy,

learned, and religious”who want to secure their lives with their own

works refuse “to let God rule and to be God.”46 This failure to trust

in God led to the defiance of God’s other commands, according to

Luther’s interpretation of the Decalogue in the Small Catechism.47

Therefore, until sinners recognize their failure to trust in the true

God,revealed in Jesus Christ, they are blind to the depth and the root

cause of their troubles in this world. The law crushes sinful pretensions

to lordship over life in many ways, but only by driving people to

LUTHER ON THE THEOLOGY OF THE CROSS 459

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 459

the cross can it focus their understanding clearly enough to see that

the original, root, fundamental sin that perverts and corrupts life lies

in this lack of trust. When his human creatures do apprehend who

God is, in the fullness of his love, they then see themselves as his beloved

children. This perception of ourselves as the heirs of Christ and members

of the Father’s family liberates us from the bondage of caring for

ourselves and presiding over our own destinies.We are freed by Christ’s

cross to be fully human again because our Lord has made us children

of God through death to sin and resurrection to new life in him. The

success of this identity cannot be measured; the certainty of this identity

cannot be shaken. From the foot of the cross we see a grandeur in

our humanity so delightful that reason cannot comprehend it.

2. Bound Not to Trust, Liberated to Trust. But the fallen human nature

cannot fear, love, and trust in God above all things. A vital part

of Luther’s theology of the cross is his recognition of the impossibility

of turning ourselves back to God, of the boundness of human

choice. He did not deny that sinners have an active will, as is sometimes

suggested by scholars who have not read his De servo arbitrio

carefully. He did deny that the sinful will is free to choose God as

long as it remains caught and trapped by its need to supply an identity

for its person since it does not recognize God as creator and giver

of our identity. “Free will, after the fall, has the power to do good

only in a passive capacity, but it can always do evil in an active capacity,”

48 Luther explained to the Augustinians in Heidelberg. Like

water, which can be heated but cannot heat itself, the will is driven

by Satan or by God, as it acts in the vertical sphere of life. Instead of

trusting the Word of the Lord,we turn to the lie of the Deceptor,49

and doubt binds our wills as it deafens our ears. Freedom comes only

through the new identity given through Christ’s death, that becomes

our death to captivity and deception.

Under the illusion that God will provide grace enough to supplement

the efforts of our own strivings—up to 99.9 percent if necessary—

those who claim that they can freely exercise enough of their

damaged will, at least to accept what God offers, are never able to

understand what Jesus meant when he said that we must be born

anew to enter the kingdom of God.50 Indeed, striving for the standards

people set for themselves can convince them that they are not

460 LUTHERAN QUARTERLY

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 460

able to reach their goals, but apart from the perspective at the foot

of the cross they will not understand that the solution lies not in trying

harder but in dying to their sinful identity. At the foot of the

cross sinners finally lose the presumption that they simply must

stretch a bit higher. They fall to the earth to die to their sinful identity.

Forde labels the claim that some human contribution,how minimal

a mite it might be, can secure human life “effrontery.” He compares

the vanity of such impertinence to what has to happen to the

addict: “a ‘bottoming out’ or an ‘intervention.’ . . . there is no cure for

the addict on his own. In theological terms,we must come to confess

that we are addicted to sin, addicted to self, whatever form that

may take, pious or impious.”51

Thus, the theology of the cross reveals that it is hopeless to hope

that human performance of any kind can contribute to improving

our status in God’s sight. Recognizing that we are no more and no

less than creatures frees us from the need to assume the impossible

burden of being the God who orders and frees our lives. Luther’s “let

God be God” lets us be us, creatures who can be all that he made us

to be.

3. Born Anew. For God has made us anew. He is the Re-Creator

as well as the Creator, and his work of re-creation has taken place on

the cross and in Christ’s resurrection. From this throne of the cross

God does our sinful identity to death and gives us new birth as his

children.God is in charge.He is Lord.He determines who his human

creatures are.

From the foot of the cross, Luther confessed, the bent and broken

shape of humanity in flight from, in revolt against, God can be seen

for what it is. The fundamental fact of human existence after the fall

is that sin pays its wage,52 and sinners receive what they have earned

through their doubt of God’s Word and defiance of his lordship—

death. Reflecting on Jesus’ conversation with Nicodemus,53 Forde

writes, “No repairs, no improvements, no optimistic encouragements

are possible. Just straight talk:‘You must be born anew.’ ”54 Sinners

must die, eternally or baptismally. The children of God become his

children not by recovering from serious illness but by being born

anew, and that new birth presumes death to the old, sinful, identity.

For God confronted both kinds of human sinfulness on the cross—

LUTHER ON THE THEOLOGY OF THE CROSS 461

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 461

the symptoms and the root sin of doubt, denial, and defiance of himself.

His declaration of war against them seized the victory in the battle

at Calvary, and he delivers the fruits of the victory in baptism55

and in the return to baptism in daily repentance.

“When Christ calls a person, he bids him come and die,” Dietrich

Bonhoeffer observed. “Every command of Jesus is a call to die, with

all our affections and lusts. But we do not want to die, and therefore

Jesus Christ and his call are necessarily our death as well as our life. The

call to discipleship,the Baptism in the name of Jesus Christ,means both

death and life.”56 By incorporating fallen human creatures into the death

and resurrection of Jesus Christ through baptism, the Creator has repeated

his modus operandi of the first week,at the beginning.He brings

forth a new creature through the creative power of his Word.

Adam and Eve were not given a probationary period in which to

demonstrate that they were worthy of their humanity. It could not be

earned. It was a gift. Human performance—proper human behavior—

flows from the gift of identity, the gift of life.Human identity as

child of God cannot be earned. It must be passively received.For those

addicted to sin, as for the alcoholic, “Thou shalt quit!” is a salutary

command, “but it does not realize its aims but only makes matters

worse. It deceives the alcoholic by arousing pride and so becomes a

defense mechanism against the truth, the actuality of addiction.”57

Law-ism, behavior-ism, tells the sinner the same kind of lie. The theology

of the cross labels as a lie the idea that human performance can

establish human identity as a child of God and a true human being.

Beyond this denial of the nature of the evil that captivates us, in

our rejection of the love of our Creator, sin also prevents us from

perceiving clearly the height of our own possibilities as people freed

from sin, law, death, and the devil. We have been liberated from slavery

to all that focuses life on our works and ourselves. We have been

freed to love our neighbor in a way that brings the good to them

and pleasure to us which is the fulfillment of our humanity. The light

of the cross does liberate sinners from the darkness of the fears that

have driven them in upon themselves so that they can appreciate the

wonder of the creature God has made them to be. The light of the

cross generates the power to fulfill God’s plan for human living—in

a sinful world, even under the cross—and to acknowledge and appreciate

the joys of life as God’s child.

462 LUTHERAN QUARTERLY

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 462

4. Living as a New Creature. That means that the cross reveals our

true humanity to us. The cross reminds us that “ ‘we live on borrowed

time’—time lent us by the Creator.Yet we also see in the death

of Jesus on the cross our rebellion against that life, and we note that

there is absolutely no way out now except one. God vindicated the

crucified Jesus by raising him from the dead. So the question and

the hope come to us.‘If we die with him, shall we not also live with

him?’ ”58 In the cross we recognize not only the awful truth but also

the wonderful truth about ourselves.

In Christ we recognize ourselves through the Word of the Holy

Spirit. We are the forgiven children of God,with identities no longer

determined by sin but rather by the forgiving, life-giving Word of

the Lord. We are children of God, with great potential, even in the

midst of a world plagued by evil, for bringing love, peace, and joy to

those God has placed around us. The cross also makes it clear that it

is not good for human beings to be alone, according to God’s plan for

humanity.59 Gathered into God’s family by the cross, those who have

been given new life there are inevitably drawn as members of the family,

with other members of the family, into that world to demonstrate

God’s love and to call others to the cross and thus into the family.

Thus, we demonstrate this truth that we are children of God in

our actions, and we use God’s truth that we are his own as a weapon

against temptation. When Satan suggests that, while we indeed have

a ticket to heaven, our sinful identity determines who we are on

earth, until death, so that we can only live life on his terms, we can

tell him to go home. We can assert the promise of God in the cross

and smother the smoldering sparks of our inclinations to live life on

our own terms rather than God’s. For the word from the cross is a

weapon in the battle within us as well as outside us.

The theology of the cross cannot be taught and confessed without

its implications for the whole human community becoming

clear. The cruciform nature of the individual believer’s life also

stretches out the arms of the body of Christ, the church, in the direction

of those around it, within its reach.For the cross was designed

to restore the whole family of God as a family.

The cross also invades our lives in the midst of the struggles against

those desires that would lead us back to idolatrous living. The Holy

Spirit leads us constantly back to the cross to crucify our flesh, our

LUTHER ON THE THEOLOGY OF THE CROSS 463

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 463

desires to live apart from his love and his plan for daily life.Every believer

knows well the struggle that Paul confesses in Romans 7 and

8. All believers recognize that there can be no compromise with the

law of sin. We sinners must be put to death. We have been put to

death once and for all in our baptisms,but in the mystery of the continuing

force of evil in our lives, the rhythm of daily repentance leads

us again and again to the cross, to die and to be raised up.

Conclusion

Luther believed that the best view of all reality was to be had from

the foot of the cross on Calvary. The death and resurrection of Christ

parted the clouds, and he could see God and himself clearly. His theology,

the theology of the cross, performs the same function at the beginning

of the twenty-first century. In Christ it reveals God’s Godness

and our humanity. In an age of profound doubt about God’s

existence and his love the cross of Jesus Christ focuses human attention

on how God reveals himself to us as a person who loves and shows

mercy, in the midst of the evils that beset us. In Christ it shows fallen

human creatures who God really is. In an age of profound doubt about

what human life is and is worth, the theology of the cross defines

human life from the basis of God’s presence in human life and his love

for human creatures. It shows human beings who they are. Luther’s

theology of the cross is indeed a theology for such a time as this.

This essay has appeared in substantially the same form under the title

“Deus revelatus—Homo revelatus, Luthers theologia crucis für das 21.

Jahrhundert,” in Robert Kolb and Christian Neddens, Gottes Wort vom

Kreuz, Luthers Theologie als Kritische Theologie, Oberurseler Hefte

40 (Oberursel: Lutherische Theologische Hochschule, 2001), 13–34.

NOTES

1. “Heidelberg Disputation, 1518,” Luthers Werke, Kritische Gesamtausgabe, 57 vols.

Eds. J.F.K. Knaake, et al. (Weimar: Böhlau, 1883ff.), 1:362,15–19 [hereafter cited as WA].

Luther’s Works, American Edition, 55 vols. eds., J. Pelikan and H. Lehmann (Saint Louis

and Philadelphia: Concordia and Fortress, 1955), 31:53 [hereafter cited as LW].

2. “In XV Psalmos graduum, 1532/33” (1540) WA 40,III:193,6–7 and 19–20.

3. “Operationes in Psalms, 1519–1521,” here on Psalm 6:11: WA 5:217,2–3.

464 LUTHERAN QUARTERLY

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 464

4. Corpus Reformatorum. Opera quae supersunt omnia, ed. C. G. Bretschneider and H. E.

Bindweil (Halle and Braunschweig: Schwetschke, 1834–1860), 21:528–536 (2nd ed.) and

934–955 (3rd ed.).

5. Luther’s theology of the cross has been analyzed in different ways, with different accents,

by scholars. The new discussion of this topic began with Walther von Loewenich’s

Luther’s Theology of the Cross, trans. Herbert J. A. Bouman (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1976),

first published in German in 1929; it focuses particularly upon its implications for Luther’s

concept of faith and the Christian life. Philip S. Watson, Let God Be God! An Interpretation

of the Theology of Martin Luther (Philadelphia:Muhlenberg,1947), combines an analysis of the

theology of the cross in relation to Luther’s understanding of revelation and of the atonement

with his doctrine of God’s Word.Further important contributions to the topic include

Hans Joachim Iwand’s essay, “Theologia crucis,” in his Nachgelassene Werke II (Munich:

Kaiser, 1966), 381–398; Jürgen Moltmann, Der gekreuzigte Gott, das Kreuz Christi als Grund

und Kritik christlicher Theologie (Munich: Kaiser, 1972); Dennis Ngien, The Suffering of God

According to Martin Luther’s ‘Theologia Crucis’ (New York:Peter Lang, 1995);Gerhard O.Forde,

On Being a Theologian of the Cross, Reflections on Luther’s Heidelberg Disputation, 1518 (Grand

Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), and Klaus Schwarzwäller, Kreuz und Auferstehung. Ein theologisches

Traktat (Göttingen:Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2000). The topic is also treated in other standard

assessments of Luther’s theology.

6. Mark 10:42–45.

7. Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross, 72–73.

8. Ibid., 2.

9. WA 1:254,35.36; LW 31:41, Thesis 28, following the translation of Forde, On Being

a Theologian of the Cross, 112.

10. WA 1:354,26–26; LW 31:41.

11. Thesis 1 stated, “The law of God, the most salutary doctrine of life, cannot advance

a person on the way to righteousness but is rather a hindrance.” WA 1:353,15–16;LW 31:39.

12. Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross, 95–96. See also Gal. 3:13,10; Rom. 4:15,

7:10, 2:12.

13. Ibid., 97–98.

14. WA 1:354,21–22; LW 31:45, Thesis 21.

15. 1 Cor. 1:18.

16. John 1:18.

17. 1 Cor. 1:22–25.

18. 1 Kings 19:12.

19. 1 Cor. 1:18–25.

20. John 1:14.

21. Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross, 35.

22. WA 1:354,29–30; LW 31:41.

23. 1 John 4:8.

24. Rom. 6:4; Col. 2:12.

25. Rom. 6:23b, 4–18; Col 2:12–15, 3:1.

26. Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross, 76.

27. Rom. 5:6–8.

28. See the explanation of the second article of the Creed in the Small Catecheism. Die

Bekenntnisschriften der evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche. 11th ed. (Göttingen:Vandenhoeck &

Ruprecht, 1992), 511 [hereafter cited as BSLK]; The Book of Concord The Confessions of the

Evangelical Lutheran Church, eds. Robert Kolb and Timothy J. Wengert (Minneapolis:

Fortress, 2000), 355 [hereafter cited as BC]; The Book of Concord The Confessions of the Evan-

LUTHER ON THE THEOLOGY OF THE CROSS 465

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 465

gelical Lutheran Church, ed. and trans. Theodore G. Tappert (Philadelphia: Fortress Press,

1959) 345 [hereafter cited ad BC-T].

29. Phil. 2:8.

30. Rom. 6:23a.

31. E.g., in his Galatians commentary of 1535, WA 40,I:432–438; LW 26:276–280.

32. E.g. in his Galatians commentary, WA 40,I:228–229; LW 26:163–164.

33. Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross, 1.

34. John 10:10.

35. Matt. 16:24–26.

36. Neddens, “Kreuzestheologie als kritische Theologie, Aspekte und Positionen der

Kreuzestheologie im 20. Jahrhundert,” in Kolb/Neddens, Gottes Wort vom Kreuz, 35–66,

here 35–41. Neddens analyzes the work of von Loewenich, Iwand, Moltmann, Forde, and

Schwarzwäller mentioned in note 5.

37. Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross, 13.

38. Ex. 4:11; Isa. 45:7; Amos 3:6.

39. WA 18:686–690; LW 33:144–147.

40. WA 43:458,35–459,15; LW 5:43–44.

41. WA 43:459,24–32; LW 5:45.

42. WA 43:460,26–35; LW 5:46.

43. 1 Cor. 1:18–2:16.

44. Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross, 114–115.

45. BSLK, 434; BC, 311; BC-T, 303.

46. Philip S. Watson made this expression the central point of his summary of Luther’s

theology in Let God Be God!, esp. p. 64. The unclear reference in Watson’s footnote at this

point is to Luther’s Kirchenpostille, WA 10,8,1:24, 4–11; Luther’s Epistle Sermons, Advent

and Christmas Season, trans. John Nicolaus Lenker, I (Luther’s Complete Works VII) (Minneapolis:

Luther Press, 1908), 117.

47.BSLK,507–510;BC, 351–354;BC-T 342–344. The words “We are to fear and love

God” that introduce explanations to commandments two through ten echo and stand on

the basis of the first commandment,which Luther interprets, “We are to fear, love, and trust

God above all things.”

48. WA 1:354,7–8; LW 31:40, Thesis 14.

49. Gen. 3:1–5.

50. John 3:3.

51. Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross, 17, cf. 64, 94–95.

52. Rom. 6:23a.

53. John 3:7.

54. Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross, 97.

55. Rom. 6:3–11; Col. 2:11–15.

56. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship (New York: Macmillan, 1959), 79.

57. Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross, 25.

58. Ibid., 9. Cf. Rom. 6.

59. Gen. 2:18.

466 LUTHERAN QUARTERLY

LQ_16-4_04_Kolb 2/12/03 15:25 Page 466

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment